New evidence shows that the liver-related disease “hepatocutaneous syndrome” can be diagnosed in dogs even before skin lesions appear.

Title of the paper: Clinical features and amino acid profiles of dogs with hepatocutaneous syndrome or hepatocutaneous-associated hepatopathy

DOI: 10.1111/jvim.16259

#Animals #VeterinaryMedicine #AnimalHealth #DogDiseases #Dogs #Pathology #Diagnosis #LiverDisease #SkinDisease #AminoAcids

DOI: 10.1111/jvim.16259

#Animals #VeterinaryMedicine #AnimalHealth #DogDiseases #Dogs #Pathology #Diagnosis #LiverDisease #SkinDisease #AminoAcids

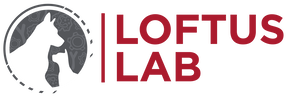

No waiting till the tail end: redefining hepatocutaneous syndrome to enable early diagnosis in dogs

Hepatocutaneous syndrome (hepato, related to the liver; cutaneous, related to the skin), also called HCS, is a rare disease observed in dogs. As the name suggests, this disease is characterized by the presence of liver abnormalities and skin lesions or rashes. Dogs with HCS also show reduced amino acid (AA) levels in the blood, with corresponding elevations in urinary AAs. Given that HCS diagnosis depends on both liver- and skin-related symptoms, dogs that show liver and AA abnormalities but no skin lesions remain undiagnosed.

It has been speculated that skin lesions represent a later stage of HCS, and their absence, therefore, cannot rule out the condition. Hence, we proposed a new, more inclusive term—aminoaciduric canine hypoaminoacidemic hepatopathy syndrome (ACHES)—to account for cases involving liver and AA abnormalities, irrespective of skin lesions. Subsequently, we attempted to test the validity of ACHES as a syndrome. We compared clinical features, pathological findings, and blood and urine AA profiles among 41 dogs with ACHES depending on skin lesion severity (no, mild, and severe skin lesions).

Interestingly, 30 dogs (73%) from the ACHES group either had skin lesions at diagnosis or developed them after some time. Dogs who had severe skin lesions at diagnosis showed poorer pathological results (example, hematocrit levels and mean corpuscular volume) than dogs without lesions. Hence, severe skin lesions seemed to indicate a higher disease stage.

Additionally, compared to dogs without ACHES, dogs with ACHES showed distinct blood AA profiles. However, within the ACHES group, blood AA profiles were similar among dogs with no, mild, or severe skin lesions, indicating that they all had the same condition. Together, the results confirmed that liver and AA abnormalities represent an early stage of ACHES, with skin lesions developing only later. Moreover, based on AA profiles, we found that some AAs—1-methylhistidine and cystathionine in the blood and lysine and methionine in the urine—could act as biomarkers for ACHES diagnosis.

Overall, our study shows the limitations related to the previous definition of HCS, which can be overcome by adopting ACHES as part of the disease definition. Accordingly, the disease can be diagnosed early based on liver and AA abnormalities and AA biomarkers, even before the appearance of skin lesions. Such early diagnosis could allow early treatment and improve health outcomes for our pawsome friends.

@wiley

It has been speculated that skin lesions represent a later stage of HCS, and their absence, therefore, cannot rule out the condition. Hence, we proposed a new, more inclusive term—aminoaciduric canine hypoaminoacidemic hepatopathy syndrome (ACHES)—to account for cases involving liver and AA abnormalities, irrespective of skin lesions. Subsequently, we attempted to test the validity of ACHES as a syndrome. We compared clinical features, pathological findings, and blood and urine AA profiles among 41 dogs with ACHES depending on skin lesion severity (no, mild, and severe skin lesions).

Interestingly, 30 dogs (73%) from the ACHES group either had skin lesions at diagnosis or developed them after some time. Dogs who had severe skin lesions at diagnosis showed poorer pathological results (example, hematocrit levels and mean corpuscular volume) than dogs without lesions. Hence, severe skin lesions seemed to indicate a higher disease stage.

Additionally, compared to dogs without ACHES, dogs with ACHES showed distinct blood AA profiles. However, within the ACHES group, blood AA profiles were similar among dogs with no, mild, or severe skin lesions, indicating that they all had the same condition. Together, the results confirmed that liver and AA abnormalities represent an early stage of ACHES, with skin lesions developing only later. Moreover, based on AA profiles, we found that some AAs—1-methylhistidine and cystathionine in the blood and lysine and methionine in the urine—could act as biomarkers for ACHES diagnosis.

Overall, our study shows the limitations related to the previous definition of HCS, which can be overcome by adopting ACHES as part of the disease definition. Accordingly, the disease can be diagnosed early based on liver and AA abnormalities and AA biomarkers, even before the appearance of skin lesions. Such early diagnosis could allow early treatment and improve health outcomes for our pawsome friends.

@wiley

Researchers have identified a promising treatment which can increase the lifespans of dogs suffering from a rare but fatal skin disorder

Title of the paper: Treatment and outcomes of dogs with hepatocutaneous syndrome or hepatocutaenous-associated hepatopathy

DOI: 10.1111/jvim.16323

#hepatocutaneoussyndrome #metabolicdisease #internalmedicine-canine #hepaticdisease #caninehealth #caninelifespan #canineskindisorders

#treatmentfordogs

DOI: 10.1111/jvim.16323

#hepatocutaneoussyndrome #metabolicdisease #internalmedicine-canine #hepaticdisease #caninehealth #caninelifespan #canineskindisorders

#treatmentfordogs

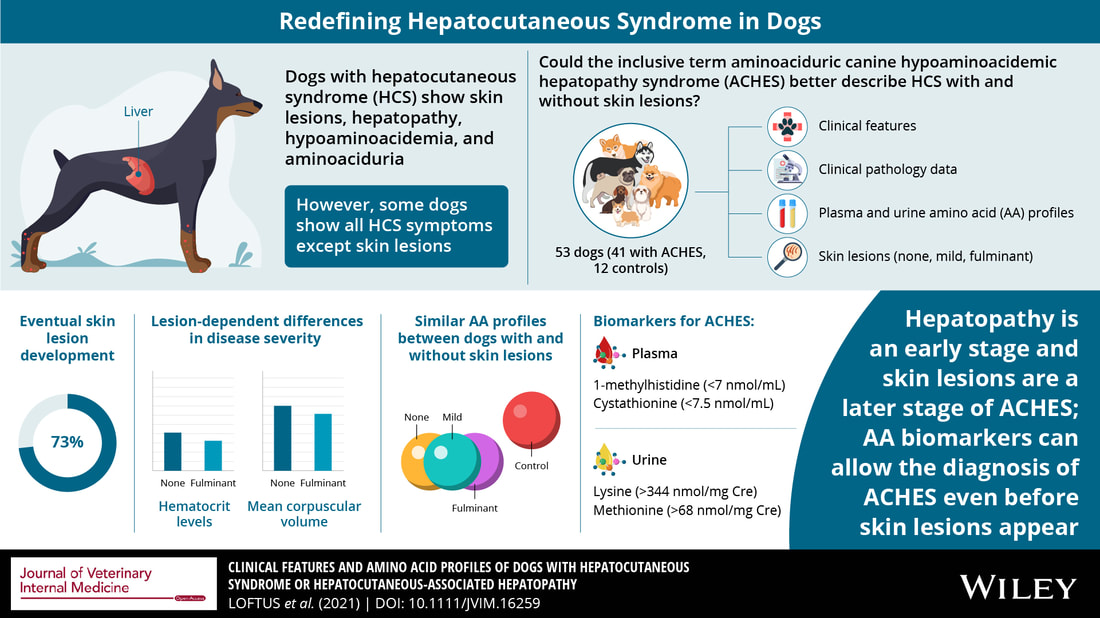

Improved survival of dogs with a fatal skin disorder: “Treating” dogs the right way

Hepatocutaneous syndrome is a rare condition linked to liver dysfunction in dogs, which usually leads to the formation of red and crusty lesions on their bodies. The development of these lesions is termed as superficial necrolytic disorder (SND), and dogs with SND generally do not survive for more than 3-6 months after diagnosis. At times, hepatocutaneous syndrome is diagnosed early, before the development of these lesions. In such cases, a broad term which defines dogs with and without SND, known as aminoaciduric canine hypoaminoacidemic syndrome (ACHES) is used.

Previously, reports have mentioned that providing a protein rich home-cooked diet and amino acid infusions may prolong the lives of dogs with ACHES. However, they have not compared the efficacy of different treatments and their outcomes.

To understand what treatments can help dogs with ACHES survive longer, we decided to study the outcomes of different diet types, number of amino acid infusions, and nutritional supplements on disease remission.

Our results demonstrated that dogs that were fed home-cooked food survived much longer than those that were fed a commercial diet. This finding may be attributed to the higher protein content in the former. Moreover, dogs who received ≥2 amino acid infusions also survived longer than those who received <2 infusions.

One of our most important findings was that dogs who received a combination treatment comprising of home cooked food, ≥2 amino acid infusions, and ≥3 supplements had the longest lifespans, and outlived dogs that did not receive such treatment.

The overall survival of the participant dogs was longer than that reported in previous studies. It is highly possible that the early treatment of dogs that had not yet developed skin lesions, was one of the many factors in their improved survival.

Thus, our study has established that with the right treatment, there is increased hope of remission in dogs with ACHES. We recommend the provision of combination treatments which can be modified for individual dogs based on their disease severity and type, for them to live longer and healthier lives.

@wiley

Previously, reports have mentioned that providing a protein rich home-cooked diet and amino acid infusions may prolong the lives of dogs with ACHES. However, they have not compared the efficacy of different treatments and their outcomes.

To understand what treatments can help dogs with ACHES survive longer, we decided to study the outcomes of different diet types, number of amino acid infusions, and nutritional supplements on disease remission.

Our results demonstrated that dogs that were fed home-cooked food survived much longer than those that were fed a commercial diet. This finding may be attributed to the higher protein content in the former. Moreover, dogs who received ≥2 amino acid infusions also survived longer than those who received <2 infusions.

One of our most important findings was that dogs who received a combination treatment comprising of home cooked food, ≥2 amino acid infusions, and ≥3 supplements had the longest lifespans, and outlived dogs that did not receive such treatment.

The overall survival of the participant dogs was longer than that reported in previous studies. It is highly possible that the early treatment of dogs that had not yet developed skin lesions, was one of the many factors in their improved survival.

Thus, our study has established that with the right treatment, there is increased hope of remission in dogs with ACHES. We recommend the provision of combination treatments which can be modified for individual dogs based on their disease severity and type, for them to live longer and healthier lives.

@wiley

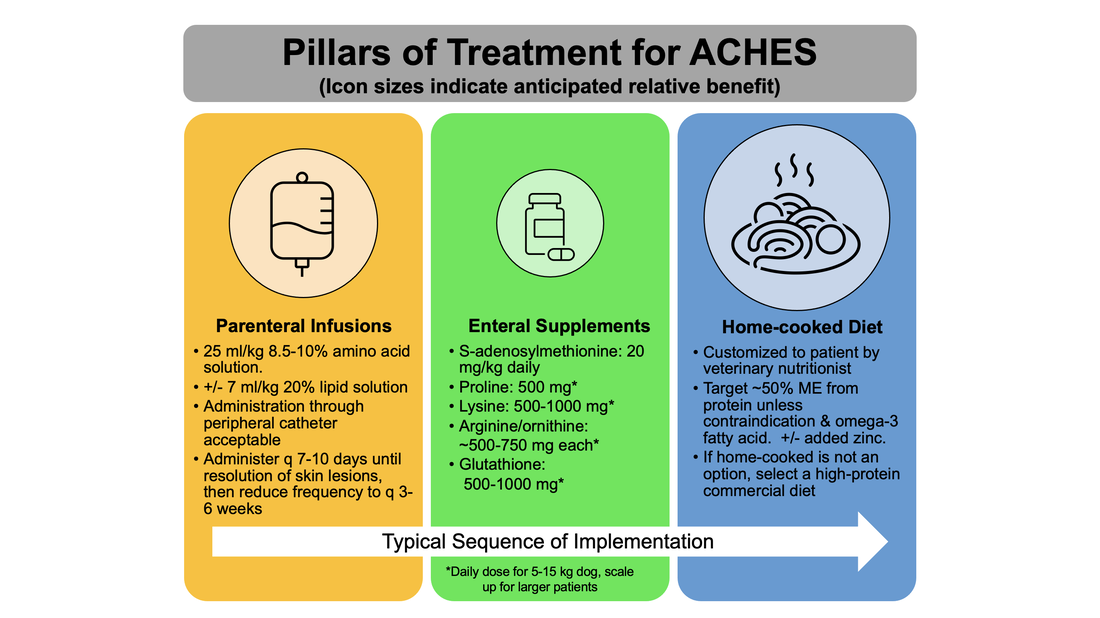

My recommended treatment strategy for dogs with aminoaciduric canine hypoaminoacidemic hepatopathy syndrome ACHES.

The typical sequence of treatment pillar implementation is not necessarily a recommended sequence and may be customized to each patient. ME = metabolizable energy. The PO supplemental zinc dose for ACHES patients is 10 mg elemental zinc/10 lbs. body weight. My supplement reommendations (From DOI: 10.1111/jvim.16323):

The typical sequence of treatment pillar implementation is not necessarily a recommended sequence and may be customized to each patient. ME = metabolizable energy. The PO supplemental zinc dose for ACHES patients is 10 mg elemental zinc/10 lbs. body weight. My supplement reommendations (From DOI: 10.1111/jvim.16323):

- S-adenosylmethionine (SAMe, Denosyl® or Denamarin®, Nutramax Laboratories)

- Arginine/ornithine (Arginine & Ornithine 500 mg / 250 mg Veg Capsules, NOW Foods)

- Glutathione (Glutathione 500 mg veg capsules, NOW Foods)

- Lysine (L-lysine, 500 mg veg capsules or Double Strength 1000 mg tablets, NOW Foods)

- Proline (L-Proline 500 mg veg capsules, NOW Foods).

- Alternative to arginine/ornithine and lysine (Tri-Amino Capsules, NOW Foods)

How do I request a home-cooked diet?

Please use our online consult form

Where can I find info about parenteral amino acid shortages?

What are some sources of amino acid solutions?